| Vossoughi, Behrouz

|

Birth name

Khalil Vossoughi

Date of Birth

11 March 1938, Khoy, Iran

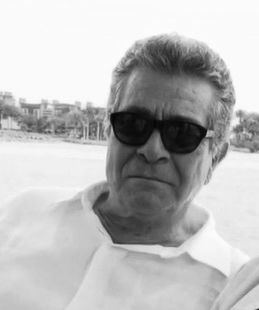

Behrouz Vossoughi (March 11, 1938, Khoy, West Azarbaijan, Iran)

Behrouz Vossoughi, born as Khalil Vossoughi 1937 in Khoy, West Azarbaijan, Iran, is an Iranian actor.

He started acting in films with Samuel Khachikian's Toofan dar shahr-e ma. He has over 40 years of experience in the motion picture industry, with featured appearances in more than 90 films.

His work has earned him recognition at several international film festivals. Vossoughi has also worked in television, radio, and theater.

YEARS GRAND prize at the San Francisco International Film Festival, the prestigious Akira Kurosawa lifetime achievement award, was slated to go to Iranian auteur Abbas Kiarostami and it nearly did.

But on being handed the trophy, the renowned director graciously announced he was accepting it instead on behalf of an exiled Iranian actor seated in the audience, Behrouz Vossoughi.

The explosion of applause from the largely Iranian audience masked the consternation that must have struck everyone else.

Abbas Kiarostami, universally acknowledged as one of the worlds best filmmakers, is also among the first of a growing number of Iranian directors whose international acclaim has brought attention to Iran as one of the more fertile grounds for filmmaking anywhere. No one disputes his importance.

But who is Behrouz Vossoughi?

Amid the applause, a handsome, dark-haired man, 50ish, in a black jacket and red tie, ascended the stage and approached the podium as Kiarostami's interpreter explained to the Farsi-impaired: This is an award for all the years hes worked in the cinema in Iran, and all the years hes awaited work here in this country. And I look forward to his return to the cinema.

The name may be unfamiliar to the rest of us, but Behrouz Vossoughi is synonymous with cinema and stardom to Iranians the world over.

More than a celebrated actor, this years S.F. International Film Festival Unvanquished honoree was one of prerevolutionary Irans biggest pop icons, a box-office Bruce Willis with the acting chops of a De Niro or Brando.

Hed already set the standard for tough-guy roles before becoming central to the Iranian neorealist new wave of the 70s.

Paired for a time, on-screen and in real life, with Googoosh the glamorous Iranian diva whose recent stadium-filling tour of the United States marked a return from 22 years of government-enforced seclusion Behrouz Vossoughi represented all the sophistication, style, and success of modern, urban Iran.

He was gossiped about in the papers and invited to parties at the Royal Court. The nation got to know him on a first-name basis. Even his hairstyle in Ghaisar the pivotal Iranian new wave film set a national trend, compelling Irans barbers to advertise a Ghaisari for any man who wanted one. You could not get bigger than Behrouz.

That was before he came to the United States. Arriving in 1978 as a visitor, shortly before the Iranian Revolution toppled the Pahlavi monarchy and led to Ayatollah Khomeinis Islamic Republic, Vossoughi ended up joining an unparalleled wave of immigration to the United States from Iran.

As the new regime came to power, it became clear to Vossoughi that he would be blacklisted if he returned to his country. He found himself indefinitely stranded in Los Angeles, relegated to an inconstant series of television bit parts and stereotyped roles in B movies.

1991s video-store vehicle, Terror in Beverly Hills, may have been the nadir of a difficult career in the United States: Vossoughi played the dreaded Middle Eastern terrorist who, in this case, kidnaps the presidents daughter.

His life has since followed the trajectory of the larger group of migrs seeking refuge in the United States, among Americans who, for years, were too ready to equate all Iranians with the demonized government they were fleeing.

Trapped within and between the politics of two nations, Behrouz Vossoughi has been living a double exile not just from his homeland, but from the cinema.

New wave, Iranian style

One hundred and eighty of Irans 400 movie houses were burned down between 1978 and 1979, the years Vossoughi began his stay in the United States, but it wasnt the first or only time film has come under fire there.

You could say Iran has always been ambivalent toward its cinema, which has been alternately beloved and reviled by the government and its opponents alike. A shah of the Qajar dynasty introduced film to Iran in 1900. But technical and economic limitations hindered the growth of a national film industry until the 1930s.

Cinema also carried the taint of Western cultural influence, a sore point for many Iranian nationalists. Muslim religious leaders labeled the early films and theaters immoral. Mobs, goaded by religious disapproval, attacked the first movie houses.

As mass opposition to Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi mounted in the late 1970s, crowds of demonstrators again torched movie theaters, along with banks and liquor stores, as symbols of Western-backed oppression.

But film was incredibly attractive to a state bent on modernization and control. It had the potential to reach the majority of a disparate and largely illiterate population.

In the years after World War II, with the support of both the Iranian and American governments, entrepreneurs gradually made movies the entertainment of the masses.

Later, under the Ministry of Culture and Art, the Iranian state cultivated avant-garde film as part of a bourgeois cultural policy meant to bolster the governments prestige abroad and thereby maintain its authority at home.

It was in both the film of mass entertainment and this new art-house cinema that Behrouz Vossoughi made his name.

Vossoughi, the oldest of five sons, was born in a small Azerbaijani town in 1938 but raised in Tehran. As he described it to me in an interview near his home in Sausalito, his early attraction to acting made the decision to become an actor a simple one.

Telling his parents was another matter. His father, like other very religious men in 1950s Iran, did not go to the cinema.

So Vossoughi kept his career a secret for as long as possible. When his father heard his sons name mentioned among the cast of a radio drama, he lied. I tried to explain to him, there are a lot of Behrouz Vossoughis.

Vossoughi got work dubbing films (a big business, since, owing to technical limitations, all Iranian films were dubbed). The job required carefully watching the same sequence over and over, and Vossoughi found it good training. He landed his first film role with The Hundred-Kilo Groom (1961), and was an immediate hit.

As a darkly romantic leading man, he made a series of adventure films and romances before the end of the decade, winning his fathers approval along the way, and became so big a star that Tehrans producers colluded to cap his salary. Vossoughi felt limited, however, and by more than the opposition of the producers. It was not just a question of money.

Irans popular cinema made mostly singing and dancing entertainments, crude comedies, and treacly romances designed for mass consumption by the new urban working class. To Vossoughi, such roles no longer presented any challenge and seemed a dead end.

I wanted to have a revolution in my career; I didnt want the same career that everybody had in the cinema in Iran.

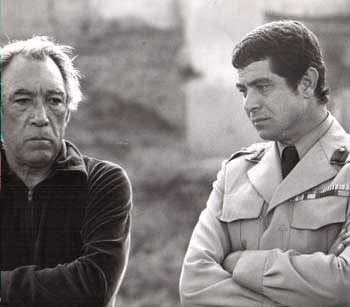

His revolution came in 1969 with Ghaisar (Caesar), a film independently produced by Vossoughi and writer-director Masoud Kimiai, later a prominent new wave filmmaker.

Based on actual Tehran police reports passed to Kimiai by a cousin in the force, the film concerned a Tehrani jahel (tough guy) who avenges the deaths of his sister and brother at the hands of a local crime ring.

The revenge plot may not have been new, but the realistic setting in Tehrans poorest neighborhoods, together with a tragic ending for the hero, helped make Ghaisar a bold departure from the typical formula. When [Kimiai] told me the story of Ghaisar, I saw something different, Vossoughi remembers. And I was right; I was really right.

Ghaisar ended up being one of two films that inaugurated the Iranian new wave in 1969. The other was Gav (The Cow), by Dariush Mehrjui, about a peasant driven mad by the death of his only cow.

Drawing on techniques and themes of the French new wave and Italian neorealism, Ghaisar and Gav debuted a gritty realism that took as its subject ordinary, often desperate people suffering tragic ends in a corrupt world.

The political implications were clear. Ghaisar, which also drew inspiration from the American western, resurrected vigilante justice in the face of an ineffectual police and court system.

Gavs depiction of the futility of rural life belied the propaganda for the shahs agrarian reform policy and earned the film a government ban although, in a pattern that would be repeated under the Islamic Republic, Gavs critical success in Europe and the United States eventually convinced the authorities to allow it to be shown conditionally in Iran.

Sleek and sexy Ghaisar, meanwhile, was an unprecedented financial success at home, without the intervention of the foreign press. After a brief shelving and reediting by the censors for excessive violence, it became one of the highest-grossing films domestically in Iranian cinema history, and a new cinema was born.

Many among the new generation of filmmakers it gave rise to are making films today, including Kimiai, Mehrjui, Perviz Kimiavi, Bahman Farmanara, Bahram Beizai, and Kiarostami (who, nine years after designing the title sequences for Ghaisar, made his first feature film, Gozaresh, or The Report, in 1978).

Irans new art cinema came to represent part of the larger culture of opposition to the Pahlavi regime. It channeled the pessimism of a new generation of artists and intellectuals chafing under a corrupt political order. Its critical success expanded the audience for Iranian film at home by wooing the Westernized, educated middle classes who had formerly ignored the national cinema in favor of European and American movies. And Behrouz Vossoughi, an innovative actor with box-office draw, contributed significantly to the bridging of this gap between popular and elite cultures.

The politics of abstraction

Vossoughi would continue to make popular films, but he was now also the darling of the new wave directors. This was a unique achievement, according to Jamsheed Akrami, whose documentary on Iranian cinema, Friendly Persuasion, is currently making the rounds at film festivals. He had the dual distinction of being a bankable star for commercial projects and a very capable and versatile actor for the new wave films, Akrami says. Behrouz would not shy away from taking chances in new wave films. He would alter his physique, wear heavy makeup, or even use [i.e., dub] his own voice in these films.

Vossoughi pushed himself to embody the most complex and disparate of characters, often spending months developing a role. In his own brand of method acting, the self-taught Vossoughi slept in a mental hospital for the character of Majid, the mentally handicapped protagonist of Sooteh Delan (Broken Hearts). His performance in Gavaznha (The Deer), perhaps his finest, came from research he did in disguise among drug addicts in the mean streets of South Tehran. From the beginning, I really wanted to be different, Vossoughi says. And I really wanted to challenge myself in creating a character. Gavaznha and Sooteh Delan, he adds, were written with him in mind. They would say, Behrouz, weve been working on this script for two years for you and just you if you dont play the part, we are not going to do this movie.

Ghaisars unqualified success meant Vossoughi was now powerful enough to dictate terms to the film producers and cinema owners. Now they came to me asking, What do you want? It was a very good question. But if he had his way with the producers, the government was another story.

Although treated publicly as a national treasure and wined and dined by the royals, behind the scenes his films, and others of the new wave, were frequently censored by the shahs Ministry of Arts and Culture. There was a special section of the Ministry of Culture, 12 people who would sit down and read the story and then stamp every page, which meant that nothing could be added or subtracted from the page. And when a movie was finished they watched it to see that it matched every page of the script.

The censors, a blunt lot, were frequently gotten around. For example, Tangsir (1973), directed by Amir Naderi and starring Vossoughi, had a strongly antiauthoritarian theme. In this story of a popular uprising in the southern region of Tangestan, the villains include an exploitative merchant class backed by the police and religious authorities. The implication that a mullah could be corrupt was unheard of. But because it was based on a true story, which had been the subject of a popular book by Sadeq Chubak, and set 60 years in the past, it eluded the crude radar of the censors.

Gavaznha, released in 1975, was less fortunate, inviting the governments unwelcome scrutiny.

The last film Vossoughi made with Kimiai, it featured a sympathetic portrayal of a young communist militant named Ghodrat who hides out with an old friend, Sayyed (Vossoughi), a former idealist turned drug addict, until they are surrounded and crushed by the overwhelming forces of the states police. After it was featured in Tehrans third international film festival, where Vossoughi walked off with another award for best actor, the government ordered the picture closed. In the end, several minutes of offending scenes were excised, the ending was changed, and Gavaznha was rereleased. But the films antigovernment bias remained so overt that SAVAK, the shahs notorious secret police, interrogated and threatened Vossoughi, leaving him with no doubt as to their attitude toward roles like the one he had taken in Gavaznha. After that, every time I went out I was looking over my back, he says. For six months I was like that. It was a nightmare. I hired a bodyguard to follow me wherever I went.

Pressure from the regime plagued the new wave filmmakers as a whole. Iranian art film, then and today, has had to be subsidized by the state, but with that relationship has come the intrusion of state policy into the filmmaking process. As censorship continued to dog new wave filmmakers, content became more abstract. Criticism had to be made indirectly through symbolism and metaphor (much as in Iranian cinema today). This abstraction led some filmmakers to increasing cinematic complexity on the order of a Mohsen Makhmalbaf, and others toward a seemingly naive style of storytelling, as in many of todays child-centered Iranian films. On the whole, abstraction made the new wave films less accessible to the mass of moviegoers (one thing that Iranian cinema today doesnt have to worry about as much, since government censorship essentially eliminates all foreign competition). By the end of the 1970s, new wave filmmakers were facing the erosion not only of their audience, but also of their financial base, as the government directed its funding increasingly toward television and educational films rather than features.

But the rejection of these films in Iran was no passive affair: one of the pivotal events in the escalation of unrest in 1978 was a lethal fire set at a movie house in Abadan. The government blamed the torching of the Cinema Rex, in which more than 400 theatergoers died, on Islamic militants. But many thought the timing and location of the attack did not fit the usual pattern of protest. The theater itself was situated in a poor neighborhood, and the fire coincided with the screening of the well-known antigovernment film Gavaznha, starring Behrouz Vossoughi. The fire was therefore widely believed to have been the work of SAVAK, and it sparked waves of protest around the country, ultimately feeding the mass uprising that was Irans revolution before it consolidated under the Islamic right. Shortly after Abadan, all film production in Iran ceased. The Iranian new wave was over.

Of hostages and B movies

By 1980, Iran was no longer an obscure or exotic place to Americans. News coverage of events in and around Iran in 1978 and 1979 made Americans more aware of the country than ever before. Stories of mass demonstrations and riots highlighted the erosion of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavis power.

The shah himself who had been an ally of the United States government ever since the CIA put him squarely on the throne back in 1953 made headlines as the subject of the Carter administrations new emphasis on human rights abuses worldwide.

He was finally forced to flee Iran in January 1979; he sought asylum in the United States but was denied. The following month, after revolutionary militants briefly captured the U.S. embassy in Tehran, the State Department evacuated the families of embassy personnel and urged all U.S. citizens in Iran to leave.

In October the shah, dying of cancer, was granted entry to the United States for medical treatment, triggering angry demonstrations from tens of thousands of Iranian students residing at American universities.

But public perception changed most dramatically after a crowd of 3,000 stormed the U.S. embassy in Tehran on Nov. 4, 1979. In the end, 52 Americans were held for a total of 444 days. Carter, whose presidency would go down with the botched rescue mission he authorized in April 1980, eschewed election-year campaigning, sequestering himself in the White House to devote full attention to the crisis.

Meanwhile, the public responded with a mixture of bewilderment and outrage. Simultaneously, the political turmoil in Iran spurred an unprecedented wave of immigration to the United States, which attracted nearly half of those fleeing Iran.

Of those who came, about half would settle in California, with the vast majority in Los Angeles. In that exodus, lives of consequence and accomplishment were often traded for ones of obscurity, anonymity, and, in the atmosphere generated by the hostage crisis, often fear and alienation as well.

Vossoughi was already in Los Angeles in 1978, working on an independently produced thriller called Cat in the Cage. At the time, the political disturbances in Iran had not much concerned him. I saw they were banning theater and things like that, he says. But like many other Iranians who came over around that time, Vossoughi assumed that any day he would be free to return. I didnt see that I was guilty of anything.

I thought that if anything happened, I could still come back and work. I am an actor. But he was far too famous. Newspapers in Tehran printed his picture with the shah and the queen. In the early months of 1979, his mother warned him not to return until things cooled off. This never happened. After six or eight months, I heard that all my colleagues over there were not being allowed to make movies.

Khomeinis government banned nearly all prerevolutionary Iranian and foreign cinema. Banned, too, were all actors and entertainers whose work was deemed inappropriate or who were too reminiscent of the old regime.

The blacklist would certainly extend to Vossoughi. His very popularity now made it impossible for him to return to Iran, at least as an actor. In the meantime he had a part as an Egyptian architect in Franklin J. Schaffners Sphinx, released in 1981 on the heels of the Indiana Jones craze. Though a box-office bust, Sphinx was the work of a major director and featured top Hollywood talent (Frank Langella, Lesley-Anne Down, John Gielgud). For Vossoughi, the part suggested better things to come.

If he were temporarily stranded in the United States, at least there might be good work ahead. He had, after all, a distinct advantage over other Iranian actors in exile: he came with formidable experience. Before arriving here, he had participated in two joint projects between American and Iranian film producers, both in English, that were attempts by the Iranian film industry to penetrate the Western market.

The second of these, Caravans (1978), filmed in Egypt, starred Anthony Quinn. It was Vossoughis work in Caravans that had attracted Schaffners attention. The stint in Hollywood should have put Vossoughi in an enviable position. He enrolled in a class to bolster his English, joined the Screen Actors Guild, and found representation through the William Morris Agency.

But global events would get in the way. Though unofficial, censorship in the United States was no less real than at home for Iranian actors on the wrong side of the politics of the day. Vossoughi remembers it as a very hot time. Popular demonstrations against Iran were a common feature on the news.

Reports of vigilantism directed against Iranians and Iranian Americans were not unusual. The Iranian flag was being burned across the United States. Many Iranians lost their jobs, and many Iranian families received threats. Finding work as an Iranian actor would now prove almost impossible. Vossoughi remembers auditioning in 1980 for a role in The Black Stallion Returns, a sequel to the 1979 hit, and getting as far as a meeting with the executive producer, Francis Ford Coppola.

My agent told me that he was sure I had the part. On the last day there were only three of us left after the 150 whod originally auditioned. Then Francis Coppola came and said he had seen my rsum and that my last movie was with Anthony Quinn. Eventually he asked me where I was from. I said Iran. So he said, Thank you for coming. My agent called me later, asking why I had done this to him. Did I know how much money he had lost? I didnt understand.

His agent wanted to know why Vossoughi had not told Coppola he was Turkish or Greek. While the idea struck Vossoughi as absurd, his identity had become a serious liability. Because of the hostages in Iran, Coppola had called my agent and said I was very good, a very fine actor, but that they could not get involved with the politics right now. According to Vossoughi, this situation repeated itself many times.

Coppolas response may have been surprising, from an outspokenly political director, but it was not atypical. (His office told the Bay Guardian he could not possibly be expected to remember details of a casting decision almost 20 years old). As film scholar Hamid Naficy confirms, The [negative] stereotype of Iranians, especially because of the hostage crisis, was really very deep-rooted. In certain parts of society you wouldnt have known that such hostility existed, but in others, especially in the entertainment field, it was quite vast.

For Vossoughi, work dried up for the next four or five years. In the United States he was bizarrely associated with the new Khomeini regime that was banning his work, and in Iran with its political opposite, the toppled shahs regime, whose censure hed already suffered. He had no place to go.

I was so mad. Everywhere I went theyd say, Where are you from? and I would say Iran. Period. I lost many parts. He managed only a small role in a horror flick, Time Walker (1982), until the mid 1980s when, thanks to a contact in television (Iranian-born director Reza Badi), Vossoughi began to find work in TV, on shows including Falcon Crest and T.J. Hooker.

But even so positioned to enter the mainstream, Vossoughi found that parts for Iranians and other Middle Easterners were mostly limited to stereotypes, especially that of the Middle Eastern fanatic. Thats the irony of it all, Naficy says, the way these stars in some ways were pushed into playing stereotypes of their own country, which they probably didnt agree with. And so they ended up reproducing sometimes the typical stereotypes.

Vossoughi himself played some of these parts in Veiled Threat (1989) and Terror in Beverly Hills (1991), low-budget action films that traded on the now iconic image of the Middle Eastern terrorist. Terror cast him as a Palestinian ex-CIA informant and hostage-taker. A vehicle for Sly Stallones no-talent sibling, Frank, it was a film Vossoughi now deeply regrets making.

But options were limited, and not just for actors. Unemployment among Iranian immigrants was very high in the first half of the 1980s over 20 percent for men owing largely to the atmosphere generated by the hostage crisis. Faced with public prejudice not seen since the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, Vossoughi found himself shut out of an industry for which he was eminently qualified and in which, had circumstances been different, he would almost certainly have found work.

The comeback

One of the many ironies in the history of Iranian film, which celebrated its centennial last year, is that the Islamic Republic has made the formerly sinful medium respectable for devout Muslims. The Islamic state has a monopoly on film production and distribution. All film stock is owned by the government, and a five-step review process gives the final say not only on the content of a film but, through a three-tiered quality-rating system, also on how well it will do at the box office.

Religious people who shunned the cinema before are now attending films regularly. Theyre even allowing their children to become actors and filmmakers. There was an association before the revolution regarding popular cinema and moral corruption, Naficy notes. That sort of association has been severed. This sanitizing of cinema by Irans theocracy has also meant that women, under the chador, have been more prevalent in filmmaking than ever before.

Even more surprisingly, this postrevolutionary cinema has actually done a much better job of reaching an international audience. Despite its sophistication, the Iranian new wave never achieved the kind of international recognition its successor has. It was Irans infamous presence in the news after 1979 that has actually helped pave the way for the success of its postrevolutionary cinema, documentarian Akrami says. When the films started appearing in festival scenes, Iran was already a major newsmaker, whether it was because of the revolution, the hostage taking, the war, or a host of incessant domestic conflicts. There was a great deal of curiosity about Iran and Iranians in the rest of the world.

By the early 1990s, audiences fascinated by this enigmatic nation discovered the appeal of new Iranian films Dariush Mehrjuiss Hamoon, Bahram Beizais Bashu, Kiarostamis Close Up which defined Iranian realities in very different terms than Americans had come to expect.

Cineastes at Cannes, the Toronto International Film Festival, and Lincoln Center declared the films original and vibrant examples of a new Iranian cinema. While the Iranian new wave films before the revolution possessed the same qualities, Akrami says, they were lacking the political context that helped provide exposure for the postrevolutionary films. It must have been a bitter irony to Vossoughi that many of the directors he had worked with, then little-known internationally, were achieving worldwide recognition while he struggled to practice his craft here in the United States.

Still, like the larger diaspora to which he belongs, Vossoughi has found his situation steadily improving. One of the more dramatic improvements has been relocating to the Bay Area. I love it. I always ask myself why I was ever in Los Angeles.

Hes working on his autobiography, and in 1999 he completed work on two films of which he is justly proud, Broken Bridges (a docudrama on the plight of Azerbaijan, directed by Rafigh Pooya) and The Crossing.

The latter stands out, by his own account, as the best work he has done since leaving Iran. The Crossing a European production by an American filmmaker, Nora Hoppe is the story of Babak, an exile who has spent 20 years away from his native country of Afghanistan. It was a part Vossoughi felt very close to, and he gave it all the concentration he had used to craft his finest performances in Iran.

And while he is still unable to make a film in Iran, recently several Iranian producers have sought him out for projects to be made in Europe. He is considering some of them but has turned down three others because they were for the regime.

He finds that work philosophically impossible. I think that artists must be independent. If I belong to some group or party or something, Im limited in my work. Whatever I do is for all people. I hate politics interfering with art.

Yet, for better or worse, Vossoughi and his work as an actor have been intimately tied to politics both in Iran and in the United States. Relations between the two countries have been thawing, but his films remain officially banned in Iran, along with nearly all prerevolutionary cinema. And for actors like Vossoughi, a blacklist is still enforced.

Meanwhile, the banned films of the prerevolutionary era sit in a precarious state of desuetude, the victim of official contempt and bureaucratic neglect. Many films are in danger of disintegration. Irans new wave, representing an as yet little-known cinematic treasure for Americans, lies for the time being largely out of reach.

For Iranians, however, who continue to enjoy his films in the privacy of their own homes on bootleg videotapes, Vossoughi has not gone away. Nostalgia for prerevolutionary popular culture has a currency many Americans might find hard to appreciate. In an ongoing war of images, idealizations of the past serve as one weapon of the representatives of Irans modern diaspora against the current regime.

Just last year, an interview with Vossoughi on Voice of America his only means of addressing the Iranian public sparked a flurry of speculation and rumor in Iranian newspapers over Vossoughis imminent return, talk that was quashed in the latest attack on the free press by right-wing forces in the government. Like Googoosh, Vossoughi remains a visceral link for Iranians, both at home and abroad, to a nostalgic image of the past.

Even here in the United States where a similar, albeit subtler and more diffuse, set of circumstances has kept Vossoughi anonymous and underappreciated Kiarostamis tribute at last years film festival has jolted the public, exhibiting the same kind of power of which cinema, especially in the hands of a master like Kiarostami, is sometimes capable.

At this years San Francisco International Film Festival, English-speaking audiences in the Bay Area will have the rare opportunity to see some of Behrouz Vossoughis best work.

Paying tribute to Vossoughi as part of its Unvanquished series, founded in 1996 to recognize exceptional actors and filmmakers marginalized by politics, the festival will feature two of his films, Tangsir and Dash Akol.

As if to bring about his own wish to see Vossoughi return to the cinema, Kiarostami has set in motion in motion pictures, that is the return of an exiled actor to the big screen. -- http://www.behrouzvossoughi.com

Selected works of

Vossoughi, Behrouz

2019

Filmfarsi (2019, Documentary)

2017

Behrouz: A Legend on Screen (2017 | Documentary, Biography)

2012

Rhino Season | Fasle Kargadan (2012)

1978

Broken Hearts | Souteh Delan | Desiderium(1978)

1978

Caravans (1978)

1976

Mah-e asal | Honeymoon (1976)

1976

The Divine One | Malakout (1976)

1975

Kandu | Beehive (1975)

1973

Curse | Nefrin (1973)

1972

The Dagger | Deshne (1972)

1972

Baluch (1972)

1971

Dash Akol (1971)

1970

The Window | Panjereh (1970)

1970

The Invincible Six | Ghahremanan (1970)

1969

Gheisar | Qaysar (1969)

1968

Dozd-e Siyahpoush | The Black Suit Thief (1968)

1968

Hengameh (1968)

1966

Goodbye Tehran | Khodahafez Tehran (1966)

1965

Aroos-e darya | The Bride of the Sea (1965)

|